- The Consell has said that it intends to turn the camp where the Franco regime locked up 20,000 Republicans in subhuman conditions into a museum

- The archaeological investigation finds human remains and the campsite, but does not locate any mass graves.

Hunger, disease, torture and executions characterised the Francoist concentration camp in San Isidro close to Albatera, where 20,000 Republican prisoners were interned for almost seven months, between 6 April 1939 and 27 October of that year, many of them having previously occupied important government positions in the Republic.

There were also members of the military, journalists, trade unionists and artists who were all captured in the port of Alicante when they tried to leave Spain on the British coal ship SS Stanbrook just days before the end of the civil war.

It was the most important concentration camp of the postwar period, and now the Department of Democratic Equality intends to turn the area where the settlement was into museum, a memory centre where one of the most important chapters in Spanish history can be seen and explained, the tragedy of the Civil War, and the appalling conditions in which prisoners were kept.

The plan, of course, is long-term, with the main stumbling block being that the land, virtually all of which was ploughed up after the dismantling of the concentration camp, is private.

The San Isidro City Council, the town which currently administrates the land in which the plots are situated, intends to acquire them through a grant.

“It is important that we can now use the area, where there was once so much suffering, as a field of memories. The former site of the concentration camp is an ideal place, although it will not be the only one, since we want to establish similar places throughout the province in all of the areas that have played a significant part in our history, such as la Posición Yuste in Petrer, the El Poblet estate where the Government of the Republic was established, the last secret residence of its president, Juan Negrín, and the port of Alicante, where many of the exiles left and others were captured and sent to Albatera.

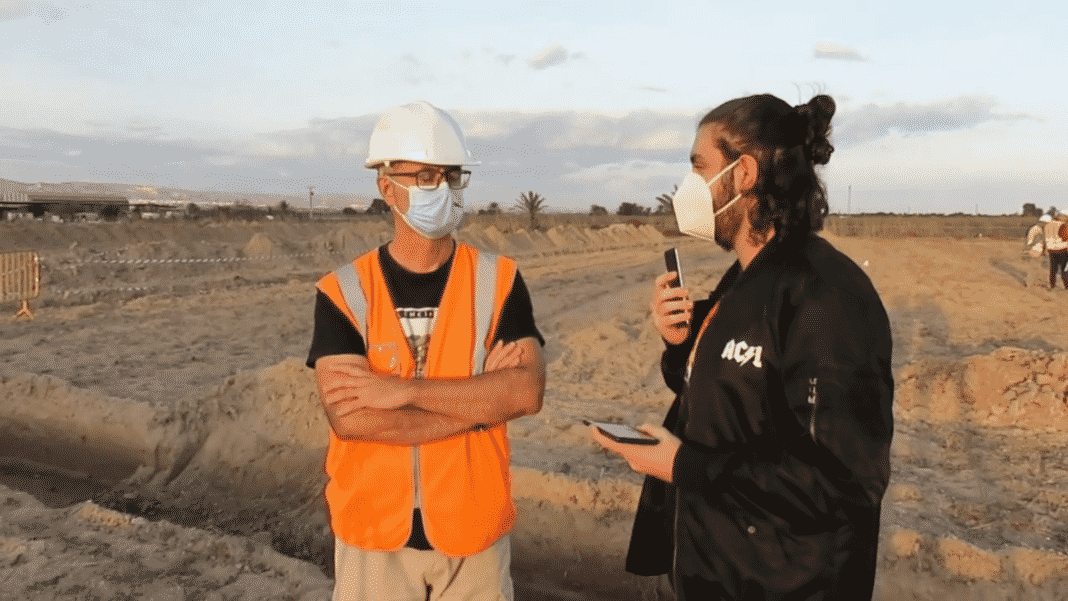

Key to the museum is the knowledge gained from the investigation directed by the archaeologist Felipe Mejías, which has just concluded in its first phase, in which he has been trying to locate a mass grave that, according to testimonies, is where an undetermined number of Republican prisoners who were shot were buried.

Although this has not yet been achieved, Mejías is happy with the findings, among them, human remains, a tibia and the occipital bone of a skull, buried a metre deep, which he says is evidence that one or more mass graves will be found on the site.

The work, which have lasted for more than a month and which have been subsidised with 17,600 euros by the Department of Democratic Quality, has been carried out with metal detectors, with a powerful geo-radar and excavations with a backhoe.

“The extension of the area is huge,” says Mejías, who plans to continue with the second part of the work next spring, for which, through the City Council of San Isidro, he has requested a further subsidy, which will allow for the exhumation of mass graves. “My intention is to extend the investigation to the entire area that the camp occupied, more than a kilometre.”

In addition to the human remains that give hope of finding one or more graves in future excavations, the exploration has found cans of sardines and lentils, the only thing that the prisoners ate and shared, bullet casings, coins and a pendant “that could all be displayed in the future museum”, says Mejías.

One more important discovery is the foundations of up to three barrack buildings, one complete with 21 pillars, a length of more than 60 metres. “In May we will excavate the area which will allow us to consider the future museum in the area,” says the archaeologist proudly. Another of the buildings found is the one that housed the cookhouse.

Mejías, who is also a historian, plans to begin the historical study of the area next month, prior to the second phase of the work that will resume in May, where he will collect more testimonies to confirm the existence of at least one mass grave.

“A resident has told me that his grandfather told him that, just at the opposite end of the area where we were digging, there were bones, at exactly the same spot where other witnesses tell us that it was the place where people were shot.”

The archaeologist is also still waiting for the final results of the georadar study carried out by the University of Cádiz that is yet to be finished. He hopes that it will provide clues to the location of the grave and the layout of the site.

Mejías says that he wants to get away from controversy. “It is not about opening wounds, but about closing them; what family members want is to know where the bodies of their loved ones are, and that is called human sensitivity, not resentment, “he says.